What Ayn Rand misses

Making Money Real is confronting for followers of Ayn Rand. Yet there is less of a difference between Rand’s philosophy and Mahinism than I imagined.

Importantly, I find that humans ordinarily survive as groups of cooperating individuals; that we are dependent on group survival, and as a result the society is more important than the individual. It is not the only value I hold, individual freedoms are important, but greed is not good.

When Ayn Rand is examined and taken as a model for social interactions, the key value offered by her is individualism. The individual is more important than the society, and society becomes stronger by allowing the strongest (most competent) free rein to do as they please for their individual profit. Greed is good.

This difference is quite stark, but the story she creates to support her notion has 3 components: heroes, theft, and villains.

Her heroes are always “competent” and reliant on nobody in their accumulation of great wealth through hard work. This is the first subtle error. Truly “great” personal wealth is not possible through the work of almost any single individual, but for a Mahinist work is the only valid source of personal wealth. Her heroes are the personification of the “Homo Economicus” of John Stuart Mill and Milton Friedman, and they always take responsibility for what they do. Her heroes are, for the most part, my heroes. They may be caricatures, but I understand them and their rebellion against the theft of their work.

The value of having individuals take responsibility is another important area in which she and Mahinism agree. Work is the source of our real wealth, and Mahi means work. Mahinism is a socioeconomic system based on work, and Mahinism agrees with the notion that there is dignity in working to provide any service or thing that the society needs. Mahinism, however, removes the possibility of anyone achieving the sort of personal wealth that distorts the fabric of today’s society. Nothing against competent workers, just a fact relating to the actual thermodynamics of the real world.

Returning to Atlas Shrugged:

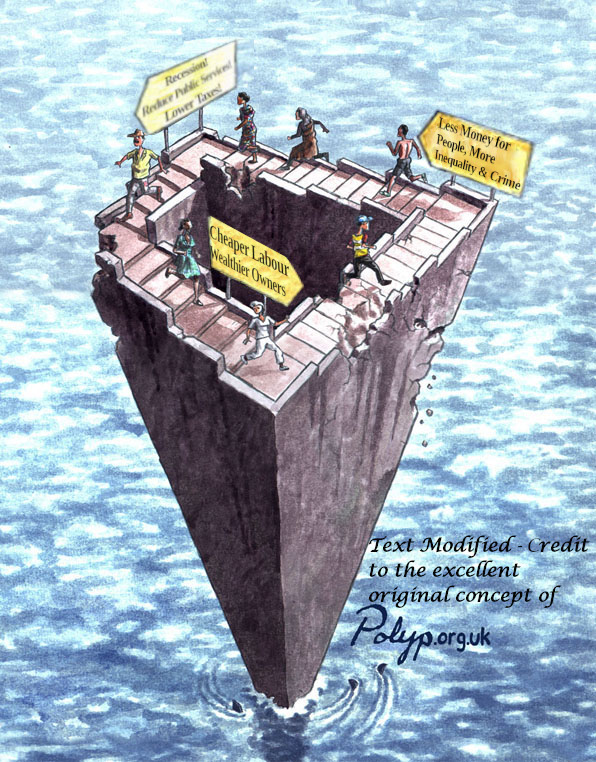

Theft occurs as heroes are stripped of their assets, and those assets are redistributed to a greedy mob of incompetents by a government under the control of the “looters.” In her story, the looters are the villains, and they are caricatures of socialists, handing out some unearned money to the undeserving poor and skimming the rest for themselves.

She correctly identifies that a theft is occurring but utterly fails to identify the thieves correctly. It is here that she and I most violently disagree, but it is a very subtle point of difference. The theft she describes is probably a real thing, but it is a trivial echo of the true and unacknowledged theft that occurs when we pay interest on loans and deposits, rent in excess of the cost of maintenance of the things we rent, and royalties on patents.

Even if we do not ourselves borrow, we are paying that interest in the price of every product we buy and every service we engage.

She spends a great deal of Atlas Shrugged building up a story about how the looters rig the game against the competent. There is scant evidence of that in the real world, and no real motivation for it apart from envy, but it is at the heart of her story. Why? Because she has to justify great wealth as being deserved wealth for her story to work and petulant envious looters are all she had. If she had not created those caricatures, she would have had to notice and admit that the real looters are not incompetent “collectivists” who envy the competent.

They were, and are, “capitalists.”

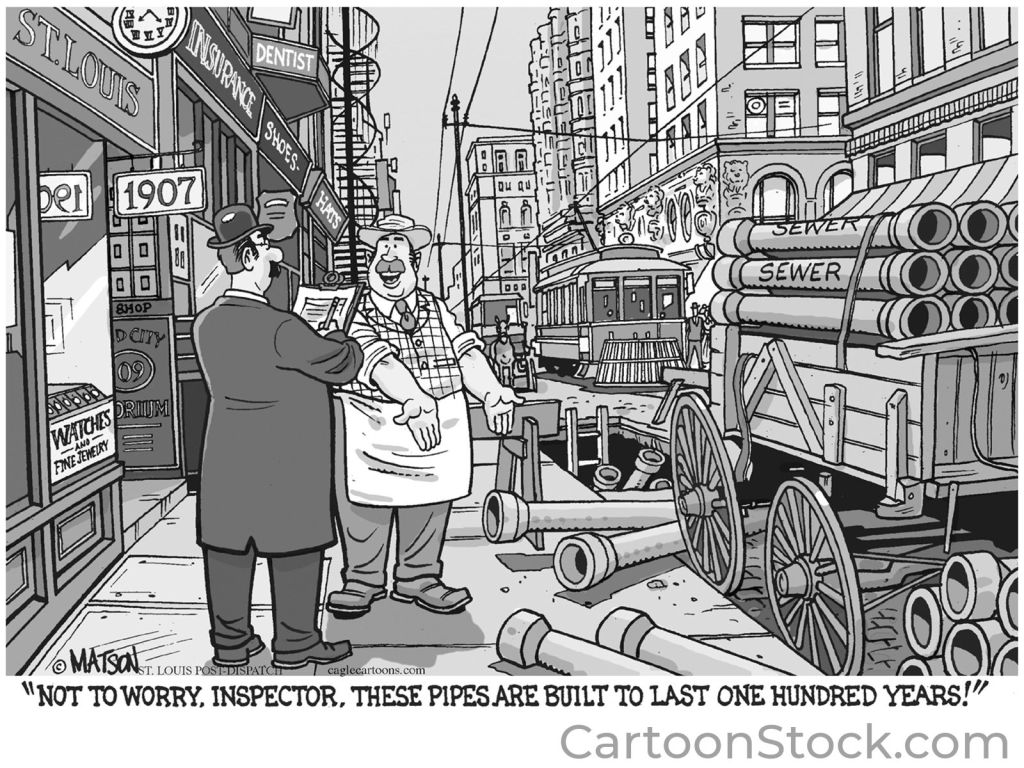

If governments are controlled by collectivist “looters” who are stealing the production of the competent through their control of the State and distributing it to the poor, why do we still have “the poor,” and how do the great fortunes of our civilization actually accumulate?

Look at where the money actually winds up! The great fortunes and increasing inequality are indisputable and massive indications that it is capitalists, not collectivists or socialists, who benefit from the theft. The wealth of the people who control our governments, our information, and through our information, us, is not gained by their production of goods or services. It is obtained by demanding, by reason of “ownership,” a share of the work of the people who do not own things: a legal theft.

She, the neoliberals, the owning class, and most of the legal systems of every government on this planet assumed that the benefits of ownership are self-propagating.

Why?

I have never even seen this concept questioned, much less seen the question answered. I do not think that even Frederick Soddy imagined this outcome of applying the laws of thermodynamics to money, but this is where it leads. The benefits are not self-propagating.

“But they worked to be able to buy the things they own and profit from!”

And they were paid for that work. Their ownership of the thing they bought cannot produce profit. If someone uses it to produce more efficiently, they are doing work, but the owner has done nothing. This is a fundamental difference between Mahinism and the beliefs of Rand or the basic socioeconomic assumptions currently afflicting most of our civilization.

Mahinism holds that the benefits of ownership are not self-propagating. It is a straightforward result of an understanding of the first law and the system boundaries that apply. That makes individual profit into an illusion that is only possible when money is not correctly defined, and money is not correctly defined in any country or city I have ever found.

As my book discusses this at length, I will not repeat it all here. Money represents work done and is limited by the laws of thermodynamics.

OUR money is not.

Her utopian society in Galt’s Gulch is powered by an engine that violates the laws of thermodynamics.

The real-world condition of making money from owning things rather than from working means that wealth is no indication of either competence or worth to society. It is a signal that a massive theft is occurring.

The key reason why her book is so potent for people who wish to obtain a superior moral justification for selfishness is the fact that we all know that we are being robbed. As Leonard Cohen’s great protest song begins “Everybody Knows.”

We are not as clear about the nature of the theft.

The only place we see money being taken from us is when we confront the tax man. Yet far more is taken from us as interest, and excess rent, and as Margrit Kennedy observes.

“A further reason why it is difficult for us to understand the full impact of the interest mechanism on our monetary system is that it works in a concealed way … interest is included in every price we pay … Therefore, if we could abolish interest and replace it with another mechanism to keep money in circulation, most of us could either be twice as rich or work half of the time to keep the same standard of living.”

Galt’s gulch has an interesting economy with an undefined currency, and a porous interface with the world of the looters. Midas Mulligan provides a lot of things to the valley that have no explained source, and Ragnar (the pirate) steals more. The justification, that they are taking back “money” taken from them by the looters, is clear. This is fundamental to the cult of Rand. The subtle theft of our attempts to violate the first law, are ignored, and it is entirely likely that Rand herself never considered that theft at all.

This is the greatest fault of Randian thought. She is profoundly logical in justifying greed, but assumes that the only source of individual wealth is individual productive work. She does not correctly identify the source of the money used either inside or outside her utopia, and over the course of the book this error leads her to believe that people who work hard for their success are being robbed blind, and that wealth is a sign of merit.

“I swear by my life and my love of it that I will never live for the sake of another man, nor ask another man to live for mine” (Rand 1999, 756)

This oath is seemingly about slavery, and it is quite reasonable if understood in that sense. Mahinism does not disagree with the prohibition of slavery. Rand uses it to deny the concept of cooperation in a society that is larger than oneself, except on the basis of enlightened self-interest. Humans are almost never this enlightened.

However, in her utopia, Rand slants off to use working” in place of the “living” discussed here; to the concepts of work and payment. Her heroes and heroines bravely take responsibility for their own survival; they work to survive, and they must produce something of value to their community to survive.

Mahinism agrees with some of her standards, but not with her assumptions, some of which are tacit, never mentioned goals.

First: The goal that her society is working towards is unquestioned, infinite, unrelenting growth. It isn’t discussed at all, it is simply assumed. It is a very common goal for all human societies because in the competition with other human societies, size matters.

Mahinism rejects this goal, because the destruction of the resources of the planet that support human civilization will stop, whether we control ourselves or Mother Nature hauls out the big stick.

Second: Wealth is not the sign of competence that she assumes it is. The wealthy almost never become wealthy because they are competent.

Competence is rare, and it is valuable to the society in which those competent people work but a more collective society (like Mahinism) can readily pay the competent a premium for their abilities. However, the people who can’t find “a decent job” in our society are not incompetent.

Third: The motivation of every socialist, or collectivist, is not to punish the competent for not allowing the incompetent to work. This is the most egregiously wrong assumption that is made by Rand and her followers. Envy does not drive us to tax the wealthy, the errors of capitalism and the broken definition of money require those taxes to fix the problems they cause.

Fourth: The strong survive; the weak perish. This is true, but it is more true of human societies than of human individuals. Compared with tigers, wolves, and sharks an individual human is woefully weak and helpless, yet the tigers are the endangered species.

Her valley is a utopia of greed. Her perfectly educated and civilized humans are such admirable, noble, meritorious specimens of our species that it is hard not to create a utopia if this is the clay of which the “common man” is formed. They are uniformly fit and of an age that they can be self-reliant for decades.

Their utopia is isolated from society: a seeming autarky that is not in truth independent. It has neither trade nor competition, but it does “tax the looters”.

Their goal is the goal of John Galt, to bring the rest of civilization crashing down to replace its rules with their own. A meritocracy in which merit is judged by the wealth controlled by its leaders.

So we see, quite clearly, the reason for the naming of the Atlas foundation, and the source of its delusions.

Leave a comment